December 3, 2025

If you’ve used traditional bar models, you know they can be helpful tools. They give students a starting point for making sense of a story. But if you’ve ever looked at a beautifully drawn bar model that’s neat and organized, with all the numbers included, and thought, “I still don’t know if this child understands the story,” you’re exactly where many teachers find themselves.

Traditional bar models are a good beginning. Structures of Equality (SoE) help us go further.

The difference often comes down to something that seems small at first glance:

Labels and descriptors.

Teachers often tell me, “We label bar models already.” That may be true, but SoE asks students to do something more precise, and that precision is what helps them make sense of what they’re being asked to do.

Traditional Bar Models vs. Structures of Equality

In many bar models, a label like “students” or “apples” feels sufficient. It names the unit, and that’s a helpful start.

In a Structure of Equality, a label is only one part of the picture. Students also need descriptors: the information that tells us which students, whose quantity, or what kind of apples.

It’s the difference between:

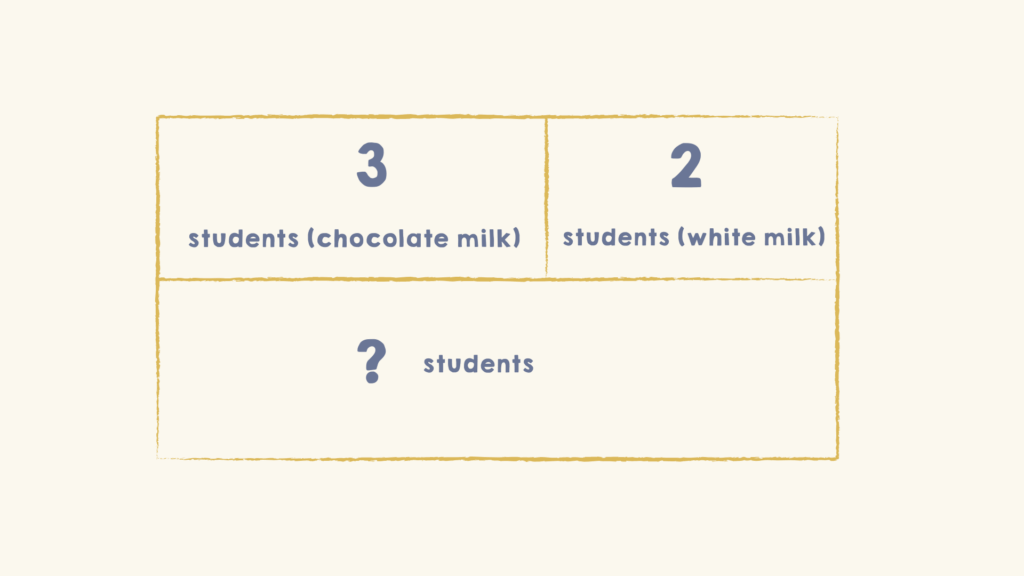

- “Students” and “students (chocolate milk)” vs. “students (white milk)”

or between:

- “marbles” and “marbles (Jordan)” vs. “marbles (Emma)”

That shift is small on paper, but big in terms of comprehension. It gives students language to make their thinking visible and to connect each number back to its role in the story.

Although there are other differences between the models, you’ll notice the labels and descriptors on the SoE help give meaning to what’s being visually represented.

What This Sounds Like in Real Classrooms

Here’s an example of the kind of exchange I hear all the time when teachers begin using Structures of Equality:

Teacher: “Tell me what this bar represents.”

Student: “Chocolate milk.”

Teacher: “Okay. And what are we counting?”

Student: “Students.”

Teacher: “Right. So how could you label it so someone who didn’t read the story would understand that we’re counting students who drank chocolate milk?”

The student pauses, then says: “Oh… students (chocolate milk).”

This isn’t a correction; it’s the moment when the comprehension becomes visible.

Students know the categories, they remember the action of the story, but descriptors help them articulate who or what each value belongs to. When they’re included, their modeling becomes clearer, more accurate, and much more connected to the meaning of the story.

Why Descriptors Matter So Much

Descriptors are where sense-making and precision meet. They tell us:

- whose quantity we’re looking at

- what distinguishes one value from another

- what each number actually means in context

Without descriptors, a model can look correct but be disconnected from the story. With descriptors, the model becomes a retell of the narrative, not just a diagram of numbers.

When students begin consistently naming both the unit and the descriptor, they start to see the relationships within the story instead of focusing only on the numbers.

As Hornburg et al. (2024) found, “mathematical language predicted development of most of the early numeracy skills (e.g., set comparison, numeral comparison, numeral identification).”

That underlines why we insist on precise naming. It’s not just good practice; it’s foundational to young learners’ numeracy growth.

Helping Students Build the Habit

This doesn’t require a new unit or a big instructional shift. It requires consistency.

Model the language you want them to internalize.

Every time you draw or discuss a structure, name the unit and the descriptor:

- “I’m labeling this as students (white milk) because it tells us which group of students we’re talking about.”

- “This one belongs to Jordan, so the descriptor will be her name.”

Students pick up precision much faster when they hear it modeled regularly.

Use questions that guide students’ reasoning.

Instead of correcting, try:

- “What’s the thing we are counting?”

- “Whose quantity is this?”

- “If someone didn’t read this story, would they understand your model from your labels?”

These questions push students to clarify their thinking, not just fix a label.

Why This Work Pays Off

Teaching labels and descriptors takes time at first, but the payoff is real and lasting. When students can name what they’re counting and which quantity belongs to whom, they reason more clearly. They understand the structure of the story, not just the numbers within it. Their models become tools for comprehension, not just drawings we hope are accurate.

Want to Learn More?

This blog is adapted from Chapter 5 of my upcoming book on Structures of Equality.

If you’re reading before Summer 2026:

You can add your name to the interest list to be the first to know when the book launches, and get access to early resources.

If you’re reading after Summer 2026:

You can dive deeper into this work inside the book, along with examples, visuals, classroom stories, and full guidance on each structure. Learn more on my website.