November 12, 2025

“How many more marbles does Jordan have than Emma?”

It seems like a straightforward question. In lots of classrooms, this question causes confusion—not because students can’t subtract, but because they don’t know what they’re being asked to understand.

Is this story about putting parts together? Finding a total? Or comparing two existing amounts?

When we don’t equip students with the right structure to interpret the situation, they default to what they know, even if it doesn’t make sense. That’s why many kids treat a comparison situation like a problem that’s asking them to find a missing part, plugging in numbers without thinking about the relationship.

This is why visual models that represent what’s happening in a story are a critical component of comprehension.

Why Comparison Situations Need Their Own Structure

Stories that describe two quantities being compared aren’t about parts forming a whole. They’re about noticing how two values relate. Unless we make that relationship visible, it stays abstract.

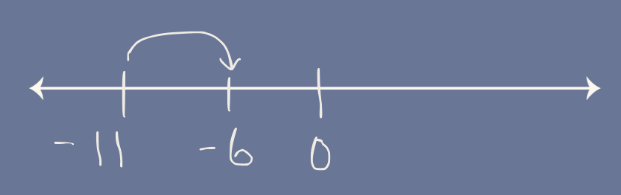

A Compare Structure of Equality (SoE) gives students a way to see that relationship: two bars, lined up at one end, with a line of equality showing where they match. The remaining space, the “more” or “extra”, is a visual representation of the difference between the two values.

a sneak peek inside Chapter 7 of the Structures of Equality book

That line of equality helps shift the focus from “what do I do with these numbers?” to “how do these values relate to each other?”

The Line of Equality: A Tool for Sense-Making

Imagine a student hears: Maya has 8 stickers. Jordan has 5. How many more does Maya have?

You could teach them to subtract 5 from 8. Or you could ask: Where do Maya and Jordan have the same amount? What’s left over?

When students draw both quantities and mark the point up to which they’re equal (the line of equality), the comparison becomes concrete. They see sameness before difference, which reflects how we naturally make comparisons in everyday life.

The takeaway is both visual and cognitive. Students aren’t memorizing a key word; they’re reasoning through a situation.

One Structure, Many Relationships

Around second or third grade, students start to see phrases like “twice as many” or “half as much.” These stories shift from additive to multiplicative comparison, but we can still model the relationship with the Compare structure.

What’s important is that students aren’t switching to a new model, they’re deepening their understanding of an existing one. The visual representation they learned in earlier grades continues to serve them, even as the math grows more complex.

What to Do With This Tomorrow

If SoE are new to you and you’re not yet familiar with the Compare structure, you can start here:

1. Swap “How many more?” for “What do you notice about the values?” or “Is there any point where these values are equal?”

When reading math stories with a comparison relationship, show students a visual model (such as snap cubes), and start with this question: Where do the two amounts match? Shift students’ attention from difference to sameness first. That subtle move changes how they interpret the problem.

2. Check for meaning, not just mechanics.

If a student draws a bar model but can’t retell the story, the model isn’t actually helping them understand the story. Ask: Can you explain what each section of your bar model shows? Have them point to what’s equal, what’s more, and what it means in the context of the story.

Why The Compare Structure Changes the Conversation

Most math tools focus on solving. Structures of Equality is a framework that focuses on comprehension.

The Compare structure, one of three SoE, doesn’t just help students get the right answer. It helps them understand what the story is about, and that’s not a small distinction. When students can’t picture what’s happening, they default to the operation they’ve practiced most. They calculate instead of think.

The structure helps them visualize the relationships occurring between the numbers and make sense of what’s happening in the story.

If This Resonated, You’re Just Getting Started

This is just an overview of one chapter from the Structures of Equality book. If you found yourself nodding or rethinking how you’ve taught math stories that ask students to compare, you’ll want to see how the rest of the book builds from here.