January 8, 2025

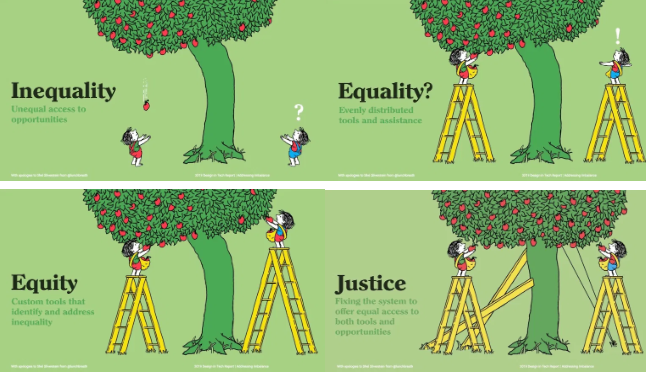

My vision for Structures of Equality (SoE) is to provide equitable access to meaningful mathematics. That’s why one of my core values is equity and accessibility. I believe all students can learn and deserve access to quality instruction.

John F. Kennedy was referring to the economy when he said “A rising tide lifts all ships”, but this idea resonates with me when it comes to education too. I recognize this doesn’t take into account all systemic inequities that exist. I’m not suggesting that a rising tide benefits all students equally, but I do believe it helps begin to level the playing field.

Providing opportunities for all students

You don’t hear me talk about differentiation when it comes to SoE. That’s because differentiation is generally defined as providing different instruction or tasks to different students, which is often not equitable.

When you give all kids the same access to a common schema, you create the conditions for them to learn the skills and concepts they need to be successful. You may need to provide additional scaffolds and support for some students, but they all have the same opportunity to rise to the level of rigorous instruction you provide.

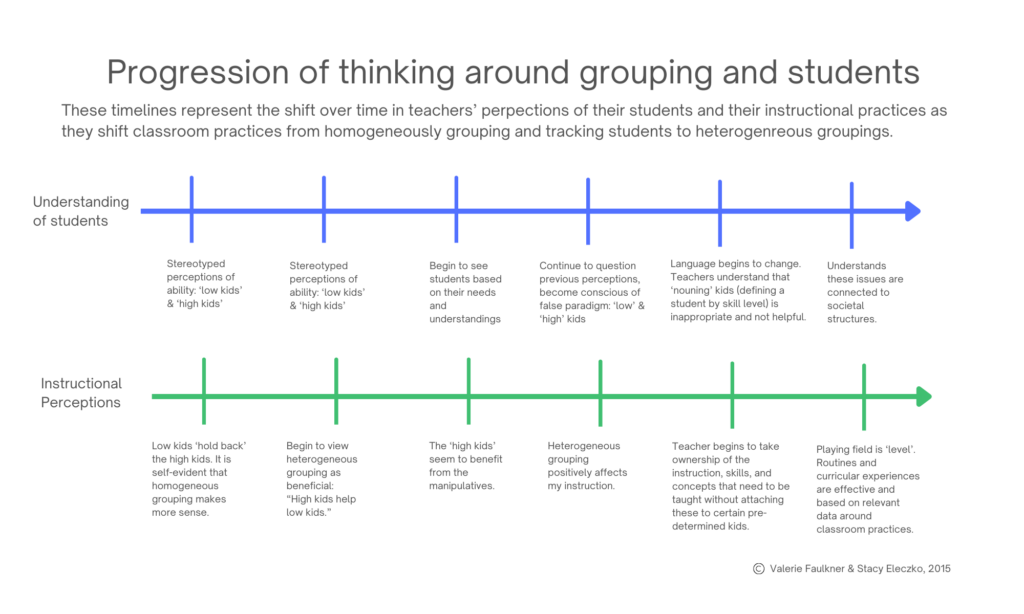

Not only does this idea apply to SoE, but it was integral to the foundation of the book I recently co-authored with Dr. Valerie Faulkner and Stacy Eleczko, The Fire & Wire Way. In 2015, they created a teacher equity trajectory based on Stacy’s work dismantling the tracking system used in the elementary school where she was an Instructional Coach.

Lessons from the classroom

Over the course of a school year, Stacy worked with administration and staff to shift from a system of homogeneously grouping kids to heterogeneous classrooms. At the end of that year, the elementary school had the highest growth in the county.

During this time, Stacy connected with Dr. Faulkner who had already been doing quite a bit of work around equity. While they were thrilled to see the increase in student academic achievement, they collected qualitative data that was equally as compelling.

They noticed subtle shifts in the perceptions of both teachers and students as they progressed throughout the school year. Using these insights, they created a continuum to show how teachers changed their perceptions around both instructional practices and their understanding of students.

Changes in beliefs

Many teachers were resistant to the change at first. Even those on board from the beginning went through major shifts in their thinking. There were concerns about not challenging the “high” students and about not giving enough time to the “low” students.

For example, one 3rd grade teacher talked about having to get all her kids used to manipulatives since she generally only used them with her “low class”. Because her “high kids” were quick and accurate, she thought they also had conceptual understanding. She mistook speed for knowledge.

She was shocked to find out that her “high kids” struggled when manipulatives were introduced. When they were forced to explain their thinking or prove it with visual models, she noticed gaps in their foundational understanding she hadn’t before.

What most teachers discovered over time, was that the idea of “high” or “low” students was a misinformed one. They were leveling students and making assumptions about what they could or couldn’t do. But when they gave all students access to the same instruction, they found kids they thought were “low” really only lacked exposure. And some who they thought were “high” didn’t have conceptual understanding.

Note, on the timeline, how these perceptions shifted over time. It wasn’t the beliefs that changed the actions of these educators. It was changing the behaviors and actions that ended up impacting their beliefs.

They found all boats can rise if they have access to the same tide. Some might need a patch or an adjustment to their boat, but we can’t address those disparities until we create optimal conditions for everyone.

Conclusion: the power of equitable access

Creating equitable access to meaningful mathematics isn’t just a vision – it’s a call to action. By challenging old assumptions and providing all students with the same opportunities to engage in rigorous instruction, we create the conditions for them to succeed. Equity doesn’t mean giving different instruction to different students. It means ensuring every student has the support they need to rise to the challenge.